Vancouver Aquarium marine scientist Laura Borden holds up a piece of kelp found in shallow waters in Howe Sound on Monday. (Rafferty Baker/CBC)

Scientists with the Vancouver Aquarium were on the water last week looking closely at how a serious decline in the Sea Star population in the waters in Howe Sound near West Vancouver is impacting the rest of the marine ecosystem.

Scientists first started noticing a decline in Sea Star populations in 2013 and the cause for the decline is what is know as, Sea star wasting disease.

“It was really striking to see the wasting sea stars. They kind of lose their internal body pressure, they develop lesions, they start to fall apart, drop their arms, so it’s really quite gruesome,” said Jessica Schultz, ecology and climate research manager with the aquarium’s Howe Sound Research and Conservation team.

Vancouver Aquarium researchers (from left to right) Donna Gibbs, Jessica Schultz, and Laura Borden gear up for a dive in Howe Sound on Monday. (Rafferty Baker/CBC)

Scientists are still struggling to fully understand the mass die-off but the disease is likely caused by a virus that is spreading between the starfish populations along the Canadian British Columbia coastline but it is now showing up in other waters from as far as Alaska to Baja, California.

“It’s definitely a big concern. It’s been called the largest wildlife mortality event that we know about,” said Schultz in an open 22-foot aluminum boat near a rocky shore, where two of her scuba diving colleagues were below the surface looking around.

Vancouver Aquarium marine scientist Donna Gibbs splashes into the water to begin a dive on Monday. (Rafferty Baker/CBC)

On this last expedition the Vancouver Aquarium’s researchers were inspecting the kelp forests that serve as protection and as a food source for an abundant number of marine species. The study is underway and they’re about halfway through a two and a half year study examining the trophic cascade.

Vancouver Aquarium researchers Laura Borden and Boaz Hung measure kelp to determine how a boom in urchins has affected it. (Donna Gibbs/Vancouver Aquarium)

A Trophic cascade means occurs when there’s an alternating effect at each level of the food chain. “Sea stars decline and their prey item — which is the urchins — increase drastically, and then [we see]the subsequent decline of their food, which is the kelp.”

“Kelp is important to the ecosystem in a number of different ways. It provides habitat for a number of different organisms, it’s a primary producer, and it’s also a way that carbon is sequestered — or stored — in the environment,” said Schultz.

Schultz pointed out there wasn’t a lot of research done on starfish before the wasting disease became more widespread because they weren’t commercially fished. But now that sea urchin populations have exploded due do lack of predation from Sea stars, kelp forests are on the decline as the ecological balance has shifted. Too many sea urchins results in less kelp. With Kelp on the decline people are now taking note because a popular food source, the spot prawn population could be negatively impacted. With 2450 metric tonnes harvested annually Spot Prawns are BC’s largest shrimp/prawn industry. The Vancouver Aquarium’s Ocean Wise programme and the Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Seafood Watch is currently listed as sustainable.

“People tend to care a lot about kelp because it can influence species that we’re interested in,” she said.

This file photo from 2014 shows an ochre sea star on the Oregon coast with one leg disintegrating from star wasting syndrome. (Oregon State University, Elizabeth Cherny-Chipman/The Associated Press)

Schultz and her team, which includes marine scientists Laura Borden and Donna Gibbs, tag individual blades of kelp, and return to make measurements over time.

“At the sites where we do have the urchins and this kelp … you’ll see where they’ve grazed them, because you’ll see little cutouts, basically, where they’ve chomped down on that kelp,” said Borden.

“In terms of the kelp, we definitely have seen it decline since sea star wasting syndrome, and we’re trying to determine how resilient it is… or isn’t,” said Schultz.

While the aquarium researchers follow the ecological impact from the dramatic loss of sea stars populations, there’s still uncertainty about whether the affected species will bounce back and how long it will take.

“The recovery of sea stars has been a big question mark. There’s even been talk of listing some species, like the sunflower star, as endangered, because we’re not sure how well they’ll be able to recover,” said Schultz.

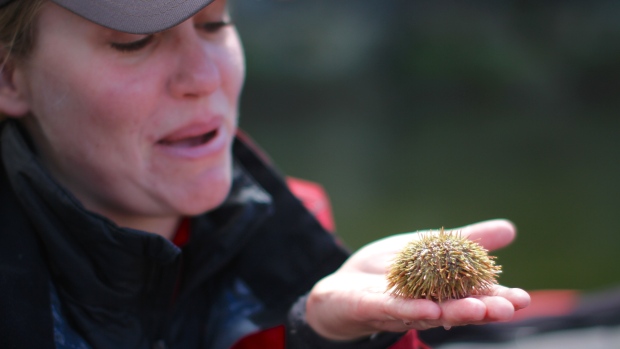

Jessica Schultz holds up one of the urchins that has flourished since a dramatic sea star die-off in Howe Sound. (Rafferty Baker/CBC)

Source – CBC.CA